Maria Chehonadskih & Andrés Saenz De Sicilia

Subject: The Global Distribution of the Ethical

Dear Reader,

It has become commonplace to speak of our current situation as exceptional and unprecedented. It is true that much of what we recognise as normal is in a state of suspension; everyday routines and rhythms are disrupted, work and sociality grind to a halt or take virtual forms whilst a disturbingly abstract numerical figure of suffering (the ‘count’) continues to accumulate. Despite the apparent strangeness of this scenario, we insist that this is not an exception but an aggressive and catastrophic affirmation of existing socio-economic logics; an intensified continuation of the rule rather than a break with it.

The pandemic reinforces existing separations, demarcations and boundaries, such that precarisation and insecurity coupled with the logics of racialisation and nationalism, regional and environmental inequalities all attain heightened force. We must not forget that this virus, like its recent zoonotic precursors, was made possible by industrial agriculture, which itself only obeys the basic compulsion to accumulate wealth that is disrupting the ecological balance of our lifeworld. The pandemic has fused and concentrated multiple states of emergencies that subsisted invisibly under the surface long before the virus took hold. If it does not present an entirely novel situation, the current moment at least confers on these states of emergency a heightened visibility, illuminating the delicate interplay between stability and crisis that is a guiding principle of neoliberal governance.

In order to guarantee the stability of accumulation and state power, the production of diffused crises of health, work and ecology is necessary. Nowhere is this crisis production for the sake of stability more transparent than in the prioritisation of the economy over the lives of the poor, the marginalised and key or essential workers, who have continued to care, clean, build, manufacture, transport and deliver during the lockdown without proper payment, security and health protection. Even though the current pandemic is far from over, what it has already posed with utmost urgency is the question of whose life matters. What is considered life and what is not? Which lives have value and deserve not to be lost? What techniques and technologies are employed to maintain and reproduce life? The ethical attention demanded by these problems is globally distributed along lines of nation, class, gender and race.

In attempting to decipher this distribution of the ethical, it would be easy and obvious to refer to emergent nationalism and projects of ethnic and cultural differentiation. The dangers they represent for those both within and outside their speculative constructs of community are clear. However, a deeper structuring principle is at work in the current conjuncture, one that determines and regulates the distribution of the ethical, of who belongs and, ultimately, who has the right to security and life.

We find ourselves at the close of a cycle of internationalist optimism. Not, of course, the internationalism of communist solidarity, but a capitalist internationalism that emerged in the wake of the collapse of the socialist states. Since 1989, the world has no longer been stratified according to allegiance with competing political projects of social organisation; two kinds of ‘freedom' bound to two superpowers, which had given social conflicts their meaning and orientation. After the collapse of the socialist project, the globe was designated a smooth space in which all conflicts were to be resolved within the sphere of property relations and market forces.

Thirty years of the global rule of capital has deflated every seductive variation on the old notion of ‘progress’, expressed after 1989 as the imperialist trope of ‘catching up’ with Western democracies, or ‘development’. Today the ideologies of promised peace, mutual benefit and institutional integration have been dismantled in favour of exclusive identities, militarised border regimes and a grim social realism that legitimates the finitude of responsibility toward other groups.

Conflictuality has been reduced to competition between national capitals, transnational corporations and new geopolitical blocs. This is why the remnants of Cold War infrastructure now serve the task of winning the competition for the place of a new capitalist and colonial superpower. The utopias are over and all that remains is the economy. Even if new geopolitical blocs mobilise the twentieth century ideologies of social justice, abuse of the old symbols should not mislead us. What brands itself as a struggle against Western or European Union domination and colonialism in fact is, in the absence of any alternative project for social existence, simply the struggle for a new configuration of geopolitical domination. This post-Cold War cynicism of competing regional capitalisms is a new framework for the distribution of the ethical.

The pandemic has only sharpened the structural tension between the totalising tendency of globalisation – the integration of production and exchange – on the one hand, and the individualising techniques of antagonistic national-cultural projects on the other. In syncopating the supposedly frictionless dynamics of the world market and global value chains, the virus discloses the invisible veins and threads of global production, the interdependency of workers across the globe, the tightness of the world rhythm of accumulation and the binding force it exerts over the lives of billions. But at the same time, the gravitation of ever more integrated economic and political forces is inverted at the level of cultural and ethical identifications and exclusions, as the artificially reproduced fantasy of economic scarcity is replayed on the stage of identity. The techniques of cultural differentiation operating here reinforce a perverse denial of our material interdependence, responsibility and collective interests. These tendencies constitute a violent contradiction at the heart of the world order in its current configuration, a play of attraction and repulsion, of interdependency and disavowal that form two sides of the same coin. In spite of the beleaguered efforts of the WHO, the absence of anything resembling effective international co-operation to mitigate the effects and spread of the virus attests to this tragic tension.

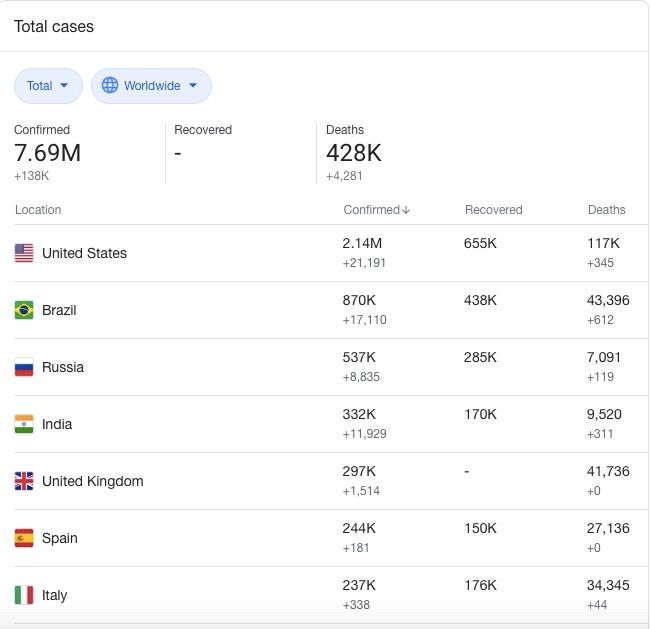

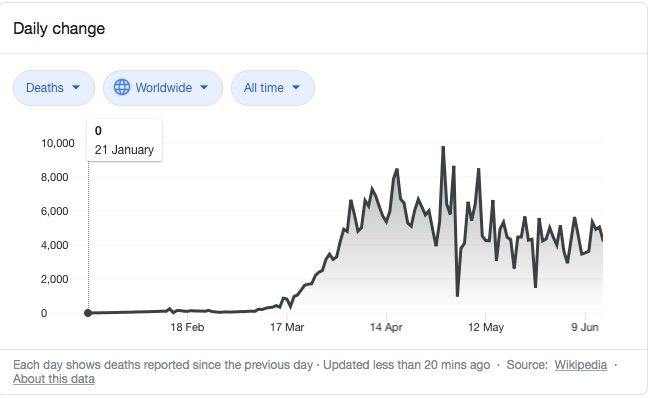

Under the rule of unimpeded international capitalism – social life with no project but competition for maximal exploitation and accumulation – the unity and condition of humanity can be registered only in abstract numbers, economic graphs and the cold balance sheet of mortality rates. ‘Success’ in this scenario has meaning only as outdoing the other, just as it does in ‘normal’ times (only GDP has now been replaced by lives lost or saved). Google the coronavirus map and you will find a competing index of nation states that registers the winners and losers of the day. The projects of differentiation and exclusion function here not only to individuate competing communities but also to erase the presence of others, such as Palestine, which will simply not appear on this map (and we know well that symbolic erasure is the pre-condition for actual annihilation). The map foregrounds geopolitical divisions, it reminds us what must be seen and how, and what should remain unseen, who gets recognition and who will remain unrecognised and stateless; virtually inexistent, before the fact. The maps and league tables affirm the pandemic as nothing but a global competition and one more theatre for the demonstration of power relations. The statistical data of cases and death tolls highlights a patriotism of local and regional technologies of pandemic management, ranging from the eugenic concept of herd immunity in Sweden and the UK (intended to secure a ‘competitive advantage’ over national economies practicing a genuine shutdown) to the old models of population control and pastoral care in East Asia.

Instead of asking why we are reduced to these statistical models and management strategies, people ask which is better: to develop herd immunity or avoid viral infection by means of heavily policed lockdown. We might ask instead why we must choose between being treated as a herd or a parish. The reduction of global community to comparative numeric calculations and death counts (‘Oh, we are not as bad as the United States!’ ‘Well, look at Brazil and Belarus, they deny the virus exists!’) redirects solidarity and mourning towards patriotic competition for the most exceptional national strategies to battle the pandemic. Clapping hands appear at the balcony not so much to celebrate key workers, but to affirm each other’s numerical representation and nationalist exceptionalism: the war effort.

This competitive regional distribution of ethical identification and responsibility springs from no natural or anthropological source (group mentality, survival instinct, etc.). Its foundation is instead the generalised ethic of indifference toward the fate of the other presupposed by a market society. Without this generalised indifference the construction or resurrection of such speculative and spectral communities would not be possible. What is affirmed in the applause is the abstract indifference of the isolated individual, of a generic social being for which there is no community or solidarity but that of the count (of property, rights, salary, health, likes, etc.).

The death count represents the highest affirmation of this abstraction; it renders mortality scientific, neutral, statistical, erasing the qualitative problem of who gets to live, who will be allowed to die and under what conditions. Even in its most radical iterations, this standpoint can only ask what constitutes an objectively ‘premature’ or ‘unnatural’ death. But all death is ultimately political, dependent on the full contour of life, from what we eat to what we earn, where we live, the air we breath and the access we have to basic services. If the limits of formal equality and the concrete problem of how the state actually treats individuals and communities are currently being contested around the most extreme terms of life and death, of police killings and the systematic denial of justice, such coarse demands cannot stop there but will have to penetrate the most private and particular regions of the individual.

Any genuinely alternative project of social solidarity will have to break through the cold indifference that is built into our lives as a social fact: those subjective mechanisms of denial that the other matters, to which we currently concede a pragmatic necessity. The same operation makes it possible to accept the crude fact of homelessness, bombs dropped elsewhere and the thousands dying unnecessarily from the virus. The UK’s annual defence budget amounts to £40 billion, meanwhile the government refuses to provide protective equipment for frontline health workers, who consequently die. We understand what this means in terms of the count, and yet cannot develop another relation to these facts. What distribution of the ethical is at work to enable this? One in which there is no collective fate but the count of each individual. The other dies. Or I die. But ‘we’ do not die.

The ethics of indifference mirrors the loss of political agency. If capitalism abstracts us as numbers and behaviour to be managed, this only means that it dehumanises us. If it is easier to sympathise with the non-human, the post-human or the unhuman, it only means that it is a symptom of the very inhuman design of capitalist society. It is true that in a sense we are already non-humans, numbers, algorithms and behaviours. But where will the simple description or self-identification with the inhumanity of this design lead us? The popular discussions on the Anthropocene often imagine that the world without humans would be a better place; ‘clean’, that if liberated from an anthropological presence nature would flourish. The self-annihilation of the human project is a symptom of tiredness and indifference. Humans are considered evil by nature, but what produces this evil is not nature, it is society: a particular kind of society, which has not and will not always exist.

We know that what is human depends on how we define what is inhuman, what is excluded and repressed. An alternative human point of view, or image of globality must be constructed against the inhumanity and indifference of capitalist power, a power that draws upon and activates traditional prejudices, resentments and hierarchies in order to inhibit the construction of a genuinely collective standpoint for action. If the tradition of past generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living, the cascade of toppled monuments to slave traders and colonial heroes expresses a struggle for liberation from long standing and still-enduring oppressions – if only as an image or metaphor, an anticipation of realising that liberation in practice.

Like the virus, such monuments attest to the concealed threads of global trade and exploitation, but here in terms of the continuity between past cycles of accumulation and the social configurations of the present. Tracing the wealth of slave owning families and nations – who were so generously compensated for their ‘losses’ following abolition – to the ruling classes of today demonstrates this irrefutably. Yet the images of transgenerational suffering torn away are also a powerful reminder that humanity is not in itself an ahistorical norm, something given and self-same in every concrete instance, but is the polymorphous capacity or task of norm-positing, of collectively determining what will count as a meaningful life, of which and what form of life matters.

About the artist

Maria Chehonadskih is a philosopher and critic. She is a Max Hayward Visiting Fellow at St Antony’s College, University of Oxford. Her research and work concentrate on Soviet epistemologies across philosophy, literature, and art, as well as on post-Soviet politics and culture. She is currently preparing a book on The Transformation of Knowledge after the October Revolution.

Andrés Saenz De Sicilia is a philosopher and sound artist based in London. His theoretical work addresses the multiple crises of modern society and the enduring relevance of philosophical concepts for making sense of these crises. He lectures at Central Saint Martins and has performed and presented works at the British Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, Cafe Oto, Villa Lontana, Whitechapel Gallery and Museo d'Arte Contemporanea di Roma.